Growing up, I was always distantly aware of Nellie Galvin’s war record. My father’s Aunt, she served as a nurse in France during World War One and was awarded a medal for bravery. After completing her nursing career, she ran The Clare Champion for many years until her death in 1967.

Beyond that, I had little information about her. I’m told she never talked about her wartime experiences and was famously reluctant to even have her picture taken.

I didn’t know if we even still had the medal until a couple of years ago, when on a visit to my aunt Maura, she showed me a couple of medals in a drawer. She knew nothing of their story, beyond the fact that the medals had belonged to Nellie and her brother, Michael, who also served in the war as a chaplain.

Although she was in great spirits that day, within a fortnight, a sudden heart attack took Maura from us and I decided that this was my cue to research Nellie’s story and hopefully, find that elusive photo.

I knew nothing about Nellie’s early life, or where she trained as a nurse, so my only hope was to find her army records. I wasn’t sure where to start but on a visit to London late last year, I made an appointment to search the photographic archives at the Imperial War Museum in Lambeth.

It quickly became apparent that I wouldn’t find what I was looking for there. The archives are indexed by places and events and since I had no knowledge of Nellie’s war, I had nothing to go on.

Generals and other top brass were indexed, but rank and file weren’t. Nevertheless, I searched the cards thoroughly for any mention of the Galvin name and found no nothing of interest.

Undeterred, I strolled over to the main museum to see what I could find. The museum was undergoing a major restoration at the time, so it was quite chaotic. The research area was intact, but again, I was out of luck.

No individual records were held at the museum, only books and other documents. For war records, I would have to visit the National Archives at Kew. Though disappointed, I sat down with a couple of books and over the course of the next hour or two, discovered more about medals than I ever thought possible.

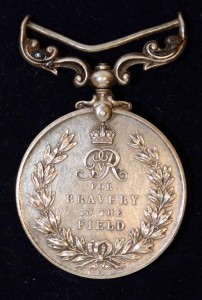

I had the medals with me that day and only then examined them properly for the first time. I had a bronze one in the shape of a star and two round silver ones, together with a couple of miniature replicas.

The interesting medal turned out to be a Military Medal, the first medal ever awarded to women, from 1916. In all, 120,000 were issued but only 127 to women, making Nellie’s medal very rare. Of those 127, just over a dozen were awarded to Irish women.

The following day I travelled to the National Archives, at Kew, an imposing building that houses an unimaginable number of records.

I hadn’t a clue what I was doing, but they’re very helpful there and I had soon tracked down a reference number for Nellie. To get her file, I would have to apply for a reader’s card and for that, I’d need photo ID. I was never more grateful for the fact that my driving licence never leaves my wallet, otherwise I would have been scuppered.

In less than half an hour, Nellie’s war record was in front of me and I was able to read her story for the first time.

She signed up as a military nurse on October 7, 1914, after training at the Meath Hospital in Dublin. Quickly posted to France, she served in a number of hospitals before moving to the No 10 Stationary Hospital and it was here where she earned her medal.

On the night of May 23, 1918, the hospital suffered a heavy bomb attack. Undeterred by the chaos, which destroyed a large part of the building, she stayed calmly at her post, attending the sick. I later found an account of the incident from the July 30 edition of the London Gazette.

“For bravery and devotion to duty during an enemy air raid when four enemy bombs were dropped on the building occupied by the hospital, causing much damage to the ward in which Sister Galvin was on night duty. She remained in the ward attending to the sick, several of whom were wounded, and carried on her work as if nothing had happened. She displayed the greatest coolness and devotion to duty.”

I think that sums it up nicely and from what I saw in her war record, it would be typical of Nellie. Her record over the years was exemplary and she never once missed a day through illness over the entire period of the war.

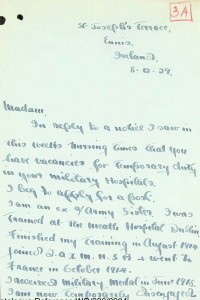

This is just one example from 1918:

“Miss Galvin is one of the best surgical nurses I have come across. She has been most favourably reported on by all the operating surgeons whose cases she had charge of.”

I left Kew a lot happier, but I still had no picture and from talking to the archive staff, had little prospect of finding one.

Slightly dispirited, that evening, I idly typed ‘Nellie Galvin military medal’ into my phone to see what would come out. The hairs stood on the back of my neck as the first result popped out of a group of nurses being presented with medals in France by General Herbert Plumer. It turns out that this photograph is very well known in military history circles. The nurses weren’t identified individually, but one of these four women was Nellie. The problem was, which one?

I immediately emailed the owner of the website. A nurse herself, she had set up the site to honour and document military nurses from the First World War. I also sent a copy back to the office, where both Tony Mulvey and Eileen McNamara had worked with Nellie and were still on the staff.

Early the following day, I had a positive ID for Nellie and hied myself back to the photographic archive where I was able to order a number of pictures taken the same day. I dealt with a man called Haughey, who was well aware of the notoriety of his surname in Ireland.

I’ve since gone back to Kew to look at war diaries for Nellie’s regiment at the time of the bombing, but they give no more useful information.

There’s an intriguing suggestion that her medal was presented again at Buckingham Palace by King George in either 1919 or 1920 and I’m told that was quite a common occurrence. I haven’t tracked that part of the story down yet, but I will.

Nellie by all accounts was a formidable woman who went on after the war to spend some time at a Tuberculosis sanatorium in Italy in 1928, before applying for a position in a military hospital in Aldershot, Kent, from the beginning of 1930. Later that year, she sailed on the H.T. Nevasa from Southampton to India and spent several months there on trooping duty before returning to work in Aldershot.

Around Christmas 1930, she looked for 22 days unpaid leave to look after a sick sister, who lived in Limerick. I think this would be Nancy, who died in 1947 and is buried with Nellie in Templemaley graveyard. While on leave, she asked to be posted to a hospital in Northern Ireland, citing her sick sister as the reason, but this was refused initially.

Eventually, in April 1931, she was posted to a military hospital in Holywood, Co Down and she remained there until she left the nursing service in July 1934.

Her annual reports were still exemplary: “She keeps her ward in very good order and has had charge of the operating room. She is able to train orderlies, is good tempered, conscientious, punctual and reliable.” “I have found her most capable, a good disciplinarian and excellent ward sister able to instruct and train orderlies. She is reliable, punctual and has common sense and good judgement. Her wards always look smart and clean.”

She took over the reins of The Clare Champion and guided it expertly for many years. As an example of her business acumen, she stockpiled newsprint in the months before the Second World War with the result that The Clare Champion never missed an issue throughout the Emergency.

Unfortunately, I never got the chance to meet and talk with her, and we still don’t have a great picture so if you knew Nellie Galvin at any point in her life, or have a picture of her, please get in touch as I’d love to hear from you.

Motoring editor - The Clare Champion

Former Chairman and voting member of Irish Motoring Writers' Association