By Owen Ryan

SOME suffering is unavoidable in life but it takes a ferocious amount of ill luck to be faced with an ordeal as horrific as that which Sonia “Sunny” Jacobs endured.

The American spent five years on death row and 17 in jail, after being in the wrong place at the wrong time, while it was worse for her partner, Jesse Tafero, who ended up in the electric chair.

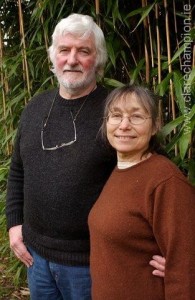

Sunny was eventually exonerated and, remarkably, she ended up marrying Peter Pringle, an Irishman, who had also been sentenced to death in 1980 after the killing of two gardaí. He was exonerated in 1995.

Both have written books about their imprisonment and are due to write one together, while Sunny will be in Glór on Sunday, March 9 as part of the Sunday Symposium on the theme of Dealing with Adversity, alongside DJ Carey; Billy Keane, journalist and author, and Michael Murphy, cancer survivor.

Sunny’s life changed forever in the early hours of February 20, 1976, as she explains.

“There was no crime going on in my case. We had just taken a lift from a friend [Walter Rhodes] of my partner at the time and we had our two children with us. It was in Florida and the driver decided to pull off the road to rest because it had gotten late. We decided to sleep in the car until it was early enough to reasonably arrive at someone’s house.

“During that time, the police came to do a routine check on the rest area and they said they noticed a gun beside the driver’s seat, which wouldn’t necessarily have been a crime, except he was on parole. When the police found that out, it turned ugly. There was gunfire. Next thing the police were on the ground and this man was ordering us into the police car and he drove away, so we were hostages of someone who had just shot at policemen. Ultimately, there was a roadblock and we were all arrested because the policemen didn’t know what to think and it went on from there.”

She says she was in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong people. Yet, even after being arrested, she believed everything would be resolved properly but the nightmare was only beginning.

“He [Rhodes] made a deal for three life sentences because he wanted to avoid the electric chair. He knew that’s what happened to anyone who killed policemen in Florida. The deal was that he would testify against my partner and me in return for his plea bargain of three life sentences and that’s what happened.

“I thought that as soon as people hear that was a bargain, they’ll know he’s the guilty one. But what I didn’t know was how the law works; that when you go to court, the jury wouldn’t be allowed to know about his plea bargain. They didn’t know. They wheel him in to testify, first against my partner Jessie, and he was convicted and sentenced to death in four days.”

Her own trial took about two weeks and one part of the case against her was the testimony of a woman, who claimed Sunny had made an admission of guilt to her.

At this stage, Sunny still had some faith in due process.

“Again I thought, ‘oh please, nobody would do such a thing’. She was a complete stranger. The jury didn’t quite believe it either and they had questions for the judge but as a result of the judge’s explanation of the law – and he had been a policeman too so I didn’t think he could be a neutral party – they felt they had no option under the law, as he explained it, to convict.”

While the jury had recommended a life sentence, Judge Daniel Futch overruled them and the death penalty was imposed.

A crazy chain of events saw her imprisoned awaiting death and, unsurprisingly, she was left floundering.

“At first I was overwhelmed. Mentally I couldn’t grasp what had just happened to me because it was against everything I had been thought to believe in all my life. There was no justice, no law. I wasn’t even sure there was a God at that point in time because how could God let that happen? This didn’t just happen to me, it happened to my whole family. My children were taken into custody until my parents could get a judge to release them. My parents, it just destroyed their life.”

For the next five years, she was left in complete isolation, her moods oscillating between fear, anger, confusion and utter hopelessness. She paced back and forth across her tiny cell repeatedly, before she had a spiritual awakening and began trying to make the best out of her dire circumstances.

“One day, I read something in the Bible, which was the only book besides the law books that I was allowed to have. I realised from that that they don’t really get to say when I die. Even though they had all the power and they could keep me there and I couldn’t leave, still my life belonged to me, even though I had to live it in that small space.

“I decided that I would believe in God because otherwise my situation would be quite hopeless and I was determined that I wasn’t going to believe in hopelessness. I had a serious conversation with God and then I decided the best thing I could do, until they figured out they made a mistake or killed me whichever one happened, was to make myself the best person that I could be in the time that I had in that place, so that when I went home to my children, I would still have something inside me to give besides anger. And if it was to be death, when I went up to meet my maker I would be the best person I could be.”

Five years after her incarceration she had her first break, when the death sentence was overturned, as the Florida Supreme Court found that Judge Futch hadn’t sufficient basis to override the jury’s recommendation of a life sentence.

Sunny’s partner, Jesse, was executed on May 4, 1990 but two years later, she was released.

“With the help of lawyers who worked for free and friends who were willing to give up their own livelihood and come down to help my lawyers to go through the masses of paperwork involved in helping someone who is wrongly convicted, they were able to win my habeas corpus, which was my last legal avenue for appeal.”

While years of struggling had paid off, she had lost a big part of her life and was left facing new challenges that she was unprepared for, with little support.

“I had no money, no identification, I had nowhere to go. My parents had died in a plane crash during the time I was in prison and my children had gone into foster care. I was 27 years old when I went in and 45 when I came out. I had no prospects for work or for anything. I went to live with some friends and basically tried to create a new life because the old one was gone.”

She attempted to rebuild relationships with her children, which was very difficult given the amount of time spent apart.

Bitterness at a system that had imprisoned her for so long would only be natural and she had to work hard to keep it from encroaching on what was effectively a new life.

“I thought I had guarded myself against that pretty well and dealt with my feelings but when I got out, I realised that I was still pretty angry so again I made a decision that the best thing I could do for myself and for my children and grandchildren was to again become the best person I could be. That meant that I had to give up the anger, which meant I had to forgive all the people that had done this to us. I set about doing that and I ended up having a beautiful life as a result but it’s not easy.”

She now lives in Connemara with Peter, who she married in 2011. Their love blossomed after she came to Ireland to address Amnesty members here.

Their shared time on death row and in prison meant they had plenty in common but she said the fact they were both using similar means to deal with the past strengthened the bond.

“When we met, he seemed to be very interested in my story and finally he told me about his story. I was amazed because he had also resorted to yoga and meditation in order to heal himself, not only while sentenced but also afterwards. That gave us a deeper bond than just the shared history of injustice. Our relationship grew from there and we decided to try to live together and thought we’d have a better life on the West of Ireland. I never regretted it.”

Sunny’s book is called Stolen Time, while her husband’s book is About Time. Further information on the couple is available on www.sunnyandpeter.com.

Owen Ryan has been a journalist with the Clare Champion since 2007, having previously worked with a number of other publications in Limerick, Cork and Galway. His first book will be published in December 2024.