John Rainsford talks to former BBC producer, Gerry Harrison, about his great-uncle’s secret diaries of the First World War.

By John Rainsford

‘Old soldiers never die (They Just Fade Away)’ says the barrack-room ballad but, with army comrades now thin on the ground, their written legacies are more crucial than ever.

The life and death of Captain Charlie May of 22 Battalion, the Manchester Regiment, also known as the Manchester Pals, are surely a case in point.

A journalist with the Manchester Evening News, he recorded his private thoughts in the lead-up to one of the darkest days of The Great War.

These intriguing insights have now been published by his great-nephew, Gerry Harrison, a former actor and director, who resides in Kilmaley.

“Charlie’s seven pocketbooks cover the period from November 7, 1915 to July 1, 1916, and the outbreak of the Battle of the Somme,” explained Gerry.

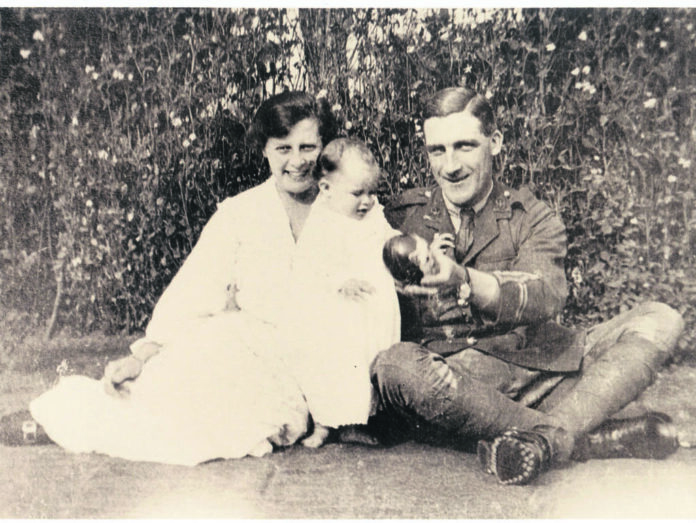

“They also served as a love letter to his wife, Maude, and their two-year-old daughter, Pauline, who spent the war in Wanstead, Essex, to be near her parents.

“All he really ever wanted to do was to get back to his wife and baby daughter. However, he enlisted willingly because of his strong sense of patriotic duty.

“Few people today have a good idea of what this war was really like but, thankfully, we have his diaries to tell us what front-line soldiers of his generation endured.”

Capt May was one of over 140,000 men waiting nervously to go ‘over the top’ on July 1, 1916, at 7.30am (zero hour), in what was to be the bloodiest day in British military history.

Ironically, while the resulting Battle of Mametz was a singular success, with May’s battalion capturing all their strategic objectives, 472 out of its 820 men were killed, wounded or missing in action.

Mr Harrison said, “In fact, the battle was equally horrific for both armies. But some things – such as the occasional mutiny – were never properly reported. In putting this book together, I certainly appreciate or better understand what very many thousands on both sides, and their families, suffered as a result of this war.

“Although born in New Zealand, Charlie was proud to be an Englishman and saw it as his duty to fight for his adopted land. However, he freely acknowledged that his wife must have been wondering why her husband was taken from her, when young men were still to be seen on London’s streets with their wives.

“Capt May held a New Zealand passport and, in 1909, joined the King Edward’s Horse, a Territorial Army Regiment, composed of men from the Dominions.

“However, his father, Charles Edward May, who was born in London, joined the New Zealand forces and saw service as a colonel in Egypt and later in France, where he heard of his son’s tragic death.”

Capt Charlie May embarked from Folkestone on November 10, 1915, bound for Boulogne. With relentless snow and rain battering their tents at night, the sound of artillery (field guns, heavy guns and howitzers) grew louder and the weapons of war (including phosphorous grenades and trench mortars) fiercer with every kilometre travelled.

Endless square-bashing, fitness-building, trench-digging and rifle drills followed. But these were of little preparation for the plagues of rats regularly infesting their waterlogged trenches.

Capt May’s uncensored memoirs were written in the mode of the Punch cartoons, using amusing and often politically-incorrect language, and not only in relation to the ‘Bosche’.

“He was not uncritical of what he termed the ‘idiocies of senior officers’ (the ‘illustrious ones’) either,” stated Gerry.

“Billeted in first-class accommodation and ‘happy as bugs in a blanket’, they frequently enjoyed sumptuous meals of steak and chips, washed down with whiskey and soda. The rank and file, meanwhile, had to make do with cattle trucks and rat holes.”

Seeking the companionship of fellow officers, Capt May enjoyed the occasional ‘first-class meal’ himself, served on ‘thin china and in dainty glasses, all resting on spotless linen’.

He also partook in football matches, riding, fishing, shooting, glee parties and sing-songs at the humourlessly named, Whiz-Bang Hall.

“I learned something of the military hierarchies of the time from the diaries,” commented Harrison. “Every officer of captain’s rank and above was entitled to a horse, although he was not in a cavalry regiment, a ‘batman’ (or orderly) and a cook.

“The officer class had total faith in the battle strategy of their superiors and, particularly, in General Sir Henry Rawlinson, who devised the failed four-day bombardment of German positions by British and French forces, using over one million shells.”

Recognised for temporary promotion when the commanding officer went on leave, Capt May’s company was subsequently assigned to the first wave of the assault.

Indeed, he organised a daring night-time raid to test the German positions, which prophetically resulted in heavy casualties, nonetheless, the ‘top men’ were pleased.

In another ‘stunt’ on a position called Bulgar Point, during the night his company suffered 30 men hit, two officers killed, one wounded and one missing.

Increasingly, Capt May’s writing reveals a growing realisation that the artillery had not been as effective as the hype had suggested.

On July 1, 1916, he recorded nervously, “No Man’s Land is a tangled desert. Unless one could see it, one cannot imagine what a terrible state of disorder it is in. Our gunnery has wrecked that and his front line trenches all right.

“But we do not yet seem to have stopped his machine-guns. These are pooping off all along our parapet as I write. I trust they will not claim too many of our lads before the day is over,” he wrote.

The Germans had dug in at the Somme as early as September 1914. Within a year, however, the front line had grown into a maze of complex overlapping pill boxes, moveable machine gun nests and hardened positions over 40-feet deep.

In February or March, Capt. May remarked, “The war is a war of endurance. Of human bodies against machines and against the elements. It is an unlovely war in detail yet there is something grand and inspiring about it.

“It makes one feel that it would be well if kaisers and ambitious, place-seeking politicians and other such who make wars could be stricken down and peaceful home-loving, ordinary men be left to live their lives in peace and in the sunshine of the love of wife and children.”

As the soldiers waited anxiously for the whistle to advance, the only instruction they received from their officers was to avoid ‘bunching’.

May’s anxiety was now discernible.

“But I do not want to die. Not that I mind for myself. If it be that I am to go, I am ready. But the thought that I may never see you or our darling baby again turns my bowels to water,” he wrote.

Only two weeks earlier, he had written of the possibility of his death. “My darling, au revoir. It may well be that you will only have to read these lines as ones of passing interest.

“On the other hand, they may well be my last message to you. If they are, know through all your life that I loved you and baby with all my heart and soul, that you two sweet things were just all the world to me,” May wrote.

Finally, once the line was launched, 50,000 men advanced across 18 miles of front at 7.30am on July 1, 1916, walking straight into killing zones created by relentless arcs of German fire.

Out of 120,000 British soldiers sent into action on day one, 19,000 were killed and 35,000 wounded, with only a fraction ever evacuated to hospital.

There were close to 50% casualties overall and thousands died in No Man’s Land of non-fatal wounds.

One of these was Capt Charlie May, himself, who was found by his orderly, Private Arthur Bunting, just outside Dantzig Alley and dragged back to the belated safety of British lines.

He was subsequently buried where he fell, aged 22 years old, in the Dantzig Alley Military Cemetery in Mametz.

In November 1916, the Battle of the Somme ended, on pretty much the same ground as it had begun, but with over one million dead from amongst the British, French and German ranks.

On a happier note, May’s trusted friend, Captain Frank Earles, later met, fell in love with and married his widow, Maude, becoming a surrogate father to his daughter, Pauline.

Capt Charlie May’s memory was honoured, however, not least by the preservation of his fascinating diaries, which detail one brave soldier’s real-time experiences of The Great War.

To Fight Alongside Friends: The First World War Diaries of Charlie May (2014) has been published by William Collins, an imprint of Harper Collins, UK. The diaries formed the basis of a major Channel 4 docudrama, directed by Carl Hindmarch, called The Somme (2005). For information about the author, visit www.gerryharrison.co.uk

A native of Ennis, Colin McGann has been editor of The Clare Champion since August 2020. Former editor of The Clare People, he is a journalism and communications graduate of Dublin Institute of Technology.