THERE is a widespread spiritual longing in Irish life, Michael Harding believes, and he feels that may account for the popularity of his own search for meaning.

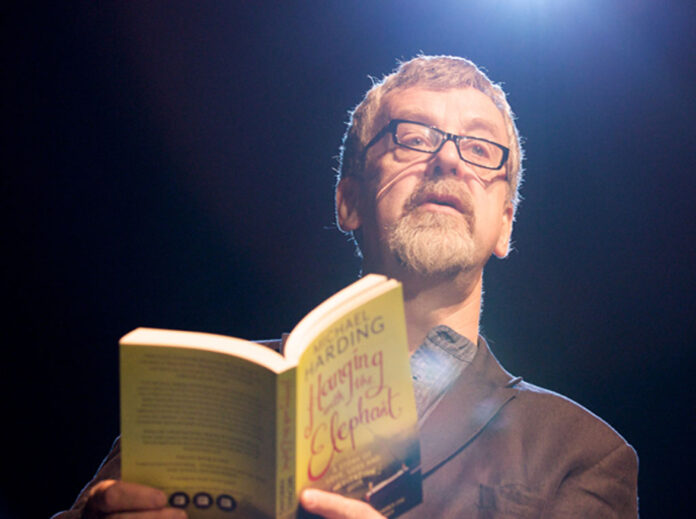

That is the theme that brought him fame, through his book, Staring at Lakes, and his Irish Times columns, while his latest book and show, Hanging With The Elephant, takes another good look at life and death.

Harding said the decline of Irish Catholicism has led to a void around the topics he goes after.

“The whole religious thing collapsed suddenly and people are still trying to figure that out. What do they do with their own isolation? What do they do with their own anxiety? As an individual, as you get older, you start thinking about what is the meaning of life, is there another life – all those deep questions. Irish people have powerful faith and I don’t think it’s gone away. I think it’s just in a process of transformation. I think the old 19th-century structures of clericalism have collapsed but I think people are still innately the same as they always were.”

He doesn’t pretend to have any solutions to the big questions and he believes this actually helps him connect with readers.

“I think people are searching and sometimes when they’re searching, it’s not that they want answers, but they want hear somebody else who has no answers. I think they find that reassuring. When I write, or when I’m on stage, I’m generally saying I’m somebody who knows nothing. At 60 years of age, I realise I’ve no answers to anything. I think that attracts people. People like that idea, that we are a bit lost but it’s okay to be lost.”

He is bringing a show based on Hanging With The Elephant around the country and he says the book is based on his experiences in the months after the death of his mother in 2012.

“She left a house behind her that kind of fell to me. It was in Cavan. You know the way when someone dies and you have to clean out the house? Sometimes it’s a thing you do very quickly. It can be all put in skips and given to the charity shops, gotten rid of.

“I thought it was hard to do that, so I ended up spending maybe two or three months going over and back and staying in the house, going through her stuff, very slowly and gradually. Going through her clothes, old files and boxes of stuff in drawers. I gradually began to kind of discover her as a human being.

“When you meet old people, you just think of them as old and, when your parents grow old, you forget that they were once younger than you are, that they once fell in love and had all the things that young people have. By going through her stuff very slowly, I kind of built up this picture of her. The book was really a way of dealing with the grieving process after losing a parent. That’s how I wrote it and that’s why I wrote it,” he says.

Worn down by old age, Harding’s mother became difficult in her latter years and he said that brought up some complicated feelings for him, both before and after her death.

“You’d be sitting there, looking at her and you’d feel, ‘God, she’s so lonely and sad’. But then you might spend only two or three hours with her and you’d be kind of glad to get away because she’d be so grumpy.

“Afterwards, you’d feel bad, to be honest. There’d have been no way she’d have come to live with me anyway – she was too proud and she wanted her own home and her own independence. But definitely, when she passed away, you’d feel sorry you weren’t able to do more for your parent.”

Until recently in Ireland, there was little encouragement for people to talk about any negative feelings and Harding says his mother’s adherence to that code of emotional Omertà led to a gap between them.

“There were things that depressed her but she never told anybody. Nowadays, everybody goes to therapists and they talk and they share their feelings and all the rest of it. But I think her generation had all the same issues of loneliness and sadness but they never had any way to share it with people so there was a communications blockage between me and her.”

Looking at his recently deceased mother’s belongings gave him a chance to see her in a fuller, and indeed warmer, light.

“You’d be going through her clothes, all her little hats and it’s funny how someone’s personality can still be in things like that. I found letters she had written before she was engaged and when she was falling in love. It was lovely.”

He feels that taking time over disposing of the belongings of a loved one is a great way to deal with grief, while he feels that grief itself needs to be fully experienced, rather than dismissed. “Often, I think, we don’t grieve enough and sometimes in the busy world we live in, we don’t realise that grief is healthy. Grief is a really natural, healthy kind of thing and you can find great peace (through it).”

Hanging With The Elephant was written over a couple of months, when he was fundamentally alone. “The wife was away, I had the house to myself, nobody here but me and the cat and I put out a programme for myself to see if I could find some kind of calmness. Really, what I found myself doing was writing the story about my mother. That’s how it came about.”

He says the show that accompanies his book is very simple. “It’s just a conversation. I read some of the book and I chat about things that come into me head. A lot of it is funny but it’s nearly like therapy for me. There’s nothing healthier than expressing your feelings when people are prepared to listen.”

Harding’s own black dog, which was central to his first book, is now quite well under control.

“I got physically ill and that led to about a year when I was very severely depressed. I believe now that there is a huge connection between depression and the chemicals in your body. I really think it’s very close to a physical disease. My physical body was damaged and that led to depression. I’ve come out of it pretty well and I think that might be because I wrote about it.”

Hanging with the Elephant: An Evening with Michael Harding will come to Glór on February 19.

Owen Ryan

Owen Ryan has been a journalist with the Clare Champion since 2007, having previously worked with a number of other publications in Limerick, Cork and Galway. His first book will be published in December 2024.