SILENT and sombre were the centenary commemoration of one of the bloodiest attacks on a Clare community during the War of Independence.

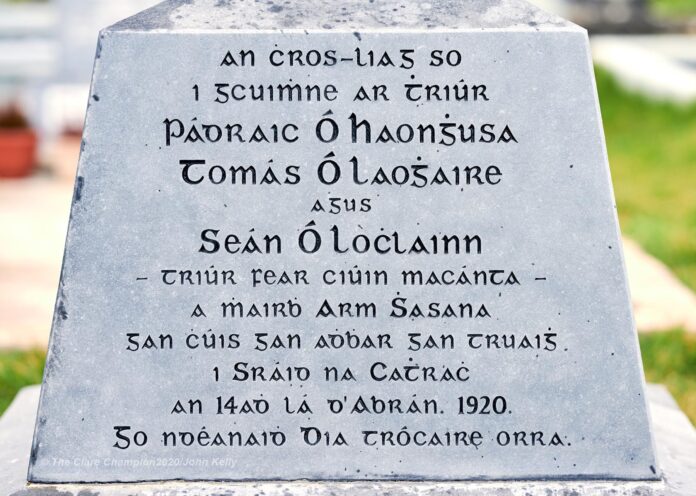

Unfortunately, due to the Covid 19 crisis, plans for the Canada Cross, Miltown Malbay commemoration, as part of Clare’s Decade of Centenaries, scheduled for Saturday, April 18, were put on hold. The community was to honour Patrick Hennessy, John O’Loughlin and Thomas O’Leary, who lost their lives at Canada Cross on April 14, 1920. Instead, the victims were remembered in the hearts and prayers of their descendants and the wider community in their homes.

Reflecting on the attack at the time, Dr Michael Fogarty, Bishop of Killaloe, said, “My poor people they have made a Calvary of your little square, but what was meant for a massacre has become a consecration.”

The families of the dead and wounded in the attack, the Mid Clare Brigade Commemoration Committee and St Joseph’s GAA Club had organised a programme that will be rescheduled when the emergency has passed.

Unknown to the people of Miltown Malbay, the chaotic handling of the Mountjoy prison hunger-strike crisis by the British authorities in Dublin Castle in April 1920 would lead directly to disastrous consequences on the streets of their town. Both convicted and remand Republican prisoners arrested in January 1920 had on April 5, led by Tom Hunter, the journalist Frank Gallagher and Peadar Clancy from Cranny, gone on hunger strike seeking political status. Dublin Castle took a hard line, but when faced by massive demonstrations, vigils in Dublin with family and friends of the prisoners arriving from around the country, the ITGW union organising a one day general strike in support of the strikers, met their demands and the British government agreed to parole for unconvicted prisoners. On April 14 confusion by the authorities reigned, of the 90 prisoners released, 31 were convicted Republicans.

Crowds gathered everywhere to celebrate a victory over the authorities; morale after over a year of war was never higher. At about 5.30pm the news reached Miltown Malbay and the community in common with the rest of the country began to come out onto the streets; the town that had been in darkness during the War of Independence began to light up.

A lighted tar barrel was carried in procession through the town and dropped to burn out in the centre of the square at Canada Cross. A crowd gathered at the burning tar barrel and several patriotic songs were sung and chorused including An Irishman’s Toast.

At about 10.45pm, as the huge bonfire blazed, The RIC, fearful of public disorder had sent for military based at the parochial hall. The combined forces approached Canada Cross with fixed bayonets from the RIC barracks at The Square through the town and lined the street at one side from the Market House to Seymour’s Medical Hall. The crowd, still singing and celebrating, was oblivious to the approaching police and Highland Light Infantry soldiers.

Captain Ned Lynch Miltown Malbay Company, 4th Battalion Mid Clare Brigade, witnessed the events that followed. “The crowd were good-humoured and were singing songs, but otherwise were orderly and in no way truculent towards anybody. I was ‘on the run’ at the time and took no part in the proceedings, but I was watching everything from Kinucane’s shoemaker’s shop about 100 yards away. During the celebrations, a party of seven or eight armed soldiers came along from their post in the Temperance Hall, passed by the crowd and went on to the RIC Barracks. After a short time, the soldiers, accompanied by some RIC men under Sergeant Hampson, left the barracks and headed straight for the crowd. As soon as they reached the outskirts, Sergeant Hampson drew a revolver, while the other policemen and soldiers took up firing positions about him. The sergeant called on the crowd to disperse and simultaneously fired from his revolver. The other police and soldiers also opened fire. People began falling all over the place and there was also a wild stampede. I saw a Volunteer named John O’Loughlin fall within a few feet of the blazing tar barrel. Thinking that he might be burned in the flames, I rushed out of Kinucane’s to his assistance. On the way I met Pat Maguire, a local blacksmith, and called upon him to help me to remove O’Loughlin. Though I was not aware of the time, Maguire himself had been wounded through the thigh, but nevertheless he helped me in carrying O’Loughlin up to Kinucane’s. Poor O’Loughlin was unconscious. After uttering an Act of Contrition into his ear, another Volunteer named “Dido” Foudy had come along and I dispatched him for spiritual and medical aid. Foudy came back in a few minutes in a most excited state. On his way to the priest’s house, he tripped over the dead body of another man who turned out to be Thomas O’Leary, a most inoffensive individual who belonged to no organisation. Foudy was again sent off to complete his errand which he did. In the meantime, I heard that Patrick Hennessy, also a Volunteer, had been killed. I went to his home to which his corpse had just been taken and remained there until the early hours of the morning when I went off to in Ballard for a few hours’ sleep. Seven or eight people were wounded as well. For the next few days the enemy forces in Miltown Malbay were confined to barracks. The village was left entirely under the control of the Volunteers. The three men who had been killed received a military funeral attended by Volunteers from all over Clare. The usual route to the graveyard was not taken and the coffins were borne past the RIC barracks and the military post. Outside the latter building the guard turned out and presented arms, but the police did not show their faces Three days after the interment the authorities decided to hold an inquest. The relatives of the deceased refused to agree to the exhumation of the bodies, while any of the British forces, police or military, were present and only consented provided the IRA did the job. The post-mortem examination was performed by Doctors Hillary, Miltown Malbay, and MacClancy, Miltown Malbay. The jury brought in a verdict of wilful murder against Sergeant Hampson and the British forces who assisted him in the shooting. Of course, no punitive action was taken by the authorities against the culprits. Public feeling against the enemy forces became very hostile following these murders in Miltown Malbay. Of their own accord, most of the local shopkeepers refused to supply them with food and drink. This boycott was called off after a few weeks because the enemy was able to obtain all his requirements from Ennistymon, nine miles away.”

Without provocation the cold-blooded murder aroused deep resentment everywhere. It galvanised the local I.R.A. and Nationalists as a wave of revulsion and grief swept the town at the indiscriminate brutal murders of the three men by Crown Forces. At the inquest the jury returned the following verdict, “We find that Patrick Hennessy, John O’Loughlin and Thomas O’Leary died as a result of shock and haemorrhage caused by bullet wounds on the night of 14th April 1920 inflicted by men of a patrol consisting of Sgt. James Hampson, Constable Thomas O’Connor, Constable Thomas Kennon, Lance Corporal Kenneth McLeod, Privates William Kilgoar, James McEwan, P. MacLoughlen, Robert Bunting and R. Adams. We find that each of the above-named members of the patrol was guilty of wilful murder without any provocation. We also condemn the other members of the patrol for their action in trying to shield those who committed the murders”.

The Dead:

Patrick Hennessy, Church Street, aged 30 years was shot dead through the chest. He was a married man with two children. He was a famous footballer and the sole support of his mother and family. Patrick played for Clare in the 1912, 1916 and 1917 Munster football finals.

John (Jack) O’Loughlin, Ennistymon Road, was a tailor and aged 25. He was shot dead through the lower intestines and hip. He lived for a short period by died after being administered the Last Rites.

Thomas O’Leary, Ballard Road, was an ex-army man and aged about 38. He was shot dead through the body and died instantly. He left a wife and 10 children.

The Wounded:

Pat Maguire, a blacksmith, James Fitzgerald, a farmer’s son, Michael J. O’Brien, an American soldier who was home on leave; Martin Moroney, wounded while standing in front of his own door,; Joe Kinnoulty, a baker; Tom Conway, a shop assistant; Thomas Reidy, a schoolboy aged 14; Nonie Donnelon, a schoolgirl. Several others received minor injuries. All were treated by both Dr Hillery and Dr MacClancy.

A native of Ennis, Colin McGann has been editor of The Clare Champion since August 2020. Former editor of The Clare People, he is a journalism and communications graduate of Dublin Institute of Technology.