By Peter O’Connell

JOHN Treacy likens what happened in West Clare 426 years ago to two fully-loaded 747s crashing, within hours of each other. On Friday, September 20, 1588, the San Marcos and the San Esteban went down off Mutton Island (Quilty) and the White Strand (Doonbeg) respectively. In the region of 780 people were drowned, while the approximate 70 survivors were executed. Both ships were part of the Spanish Armada, whose initial aim was to help the Duke of Parma’s army to cross from France to England and, having accomplished this, the Armada’s second objective was to wipe out the English fleet.

In recent months, the San Marcos Project, which is headed locally by John Treacy, a postgraduate researcher and Mary Immaculate College PHD student, has started its quest to elicit if the wreck of the doomed 790-tonne Portuguese galleon can be located.

When it sailed from Corunna, it carried 33 guns, 409 men, including 292 soldiers and 117 sailors. In addition, there were servants so it is probable that over 450 lives were lost when she broke up on the reef between Mutton Island and Lurga Point. Only four survivors were taken from the San Marcos. It has proven impossible to uncover the exact death toll from the wrecking of the ship.

“The honest answer is we will probably never know how many people were on board. Between that and San Esteban (350) in Doonbeg, you’re talking about the equivalent of two fully-loaded 747s crashing within four miles of each other,” John Treacy stated.

In their efforts to return to friendly territory, the ships were to sail by the north coast of Scotland, until they hit the Rockall bank and then onward towards Ireland’s west coast.

“If they made the turn south at Rockall, prevailing south westerly winds would mean they would have missed Cape Clear and avoided the west coast of Ireland. The weather was so unusual, they took the turn too early and prevailing winds upset their course,” John Treacy explained.

Speaking in Spanish Point, as the now benign waves rolled towards the shoreline, Treacy said that the project may establish how and why the ships were wrecked off the West Clare coast.

“One of the key things that we’re trying to achieve is to work out exactly what their intentions were. Were they coming from the north and had lost control of the ship? Or were they deliberately trying to get in behind Mutton Island to anchor to try and ride out the storm?” he queried.

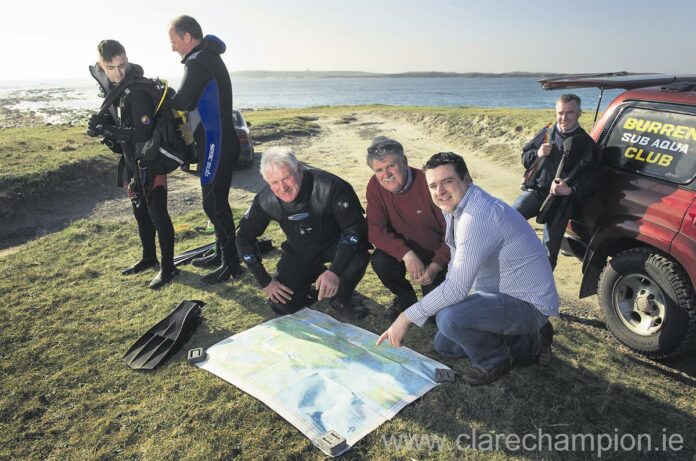

The San Marcos Project team is a multi-disciplinary group, with skills ranging from maritime history, marine archaeology, marine geology and diving. “At best, we hope to find part of the keel and maybe one of the stern posts. We probably won’t find more than that. Finding a bronze cannon would be the ideal scenario,” John Treacy said of the San Marcos, which was at sea for three months in 1588.

Unfortunately for the few surviving crew, they were soon put to death in Spanish Point.

Boetius Clancy, who was the high Sheriff of Clare, had been monitoring the ships. He was based in Knockfinn, Doolin, where he operated the Brehon Law School. Clancy had been directed by Richard Bingham, lord lieutenant of Connacht, who had been in turn ordered the lord lieutenant of Ireland, there was to be “no quarters shown” to any survivors taken from the Armada.

“That was unusual because a lot of the Armada survivors were pretty well treated. They were held for ransom or just released, whereas Ireland had gone through a period of insurrection over the previous number of years. The English were mindful of possibly thousands of Spanish troops coming ashore in Ireland and teaming up with some of the more rebellious around Ireland,” John Treacy explained.

“The O’Brien’s had aligned themselves with the Crown at that stage. They were quite pragmatic in terms of minding their estates. Clancy had monitored a flotilla of 13 ships that had travelled down, of which the San Marcos and San Esteban were at the tail-end. So he was pretty well placed when the ships floundered. He was down within a couple of hours, from the Cliffs of Moher. Clancy was helped by a guy called Nicholas Cahan, who was based down in Kilrush. He was the coroner for Clare and he was the first person on the scene at the sinking of the San Esteban,” John Treacy detailed.

While he was dealing with the fallout and the 60 survivors in Doonbeg, word came through from Ibrickane that a second, much larger, ship had wrecked. “So he immediately departed to come up and deal with that one. The seas, at that stage, were mountainous. You’re talking about at a level of what we had in January and February of this year. Because of where they had wrecked, it seems they hit some form of reef or rock,” Treacy noted.

Along with the survivors from the San Esteban, the four crew, who lived through the sinking of the San Marcos, were soon killed.

“There’s a bit of contention over where they were executed. There were two Cnoc na Crocaire’s in West Clare. One is here at the golf club but the original Cnoc na Crocaire is gone. It was excavated as a sandpit to build all the houses in Spanish Point from around 1780 onwards. They are probably buried very, very close to us here,” John Tracey revealed, as he eyed the land around the car park in Spanish Point.

“Furthermore, most of the debris and bodies washed up here. They would have been buried very close to where they were washed ashore,” he said of those who were drowned.

Malbay Films will shoot a film based on the hunt for the shipwreck, while the project manager is Fergal McGrath, who is a marine geologist, employed by the Marine Institute. The project will be overseen by Galway-based Informar. “In terms of expertise and technical ability, with Infomar, you’re really at the top of the ladder,” John Treacy pointed out.

The San Marcos Project was launched at the Armada Hotel by Spanish Ambassador to Ireland, Javier Garrigues and Clare Fine Gael TD, Pat Breen.

Project San Marcos is an initiative to bring together the best in Irish historical, archaeological and scientific fields, united in a common goal of searching for and, ultimately, excavating this important historical wreck. It draws on world-renowned expertise from the Irish Underwater Archaeology Unit (Department of Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht), INFOMARR. The INFOMAR programme is a joint venture between the Geological Survey of Ireland and the Marine Institute and is the successor to the Irish National Seabed Survey, Mary Immaculate College Limerick’s Department of History, The Old Kilfarboy Society, the Burren Sub-Aqua Club and other sub-aqua clubs around the region.

These organisations are combining their collective expertise, to search for this Armada wreck, with the support and advice of INFOMAR and UAU. It is hoped that the summer of 2014 will see the location of this great Portuguese battleship’s final resting place.

The project is fully licenced under the terms of the National Monuments (Amendment) Acts 1987 and 1994.

A native of Ennis, Colin McGann has been editor of The Clare Champion since August 2020. Former editor of The Clare People, he is a journalism and communications graduate of Dublin Institute of Technology.